All images by the ICZ

ABOUT

Singapore, December 2019 – ShanghART Singapore is pleased to present a solo exhibition by Robert Zhao Renhui, The Lines We Draw. Bringing together recent works spanning photography, video and installation, this exhibition explores migration and extinction in the natural world. Drawing from narratives from Dandong and Taiwan, China and Singapore, Zhao’s work spotlights situations of ecological interest: from the migrations of godwits and great knots over the skies of the Yalu River estuary to the eradication measures against invasive spotted tree frogs in Taipei.

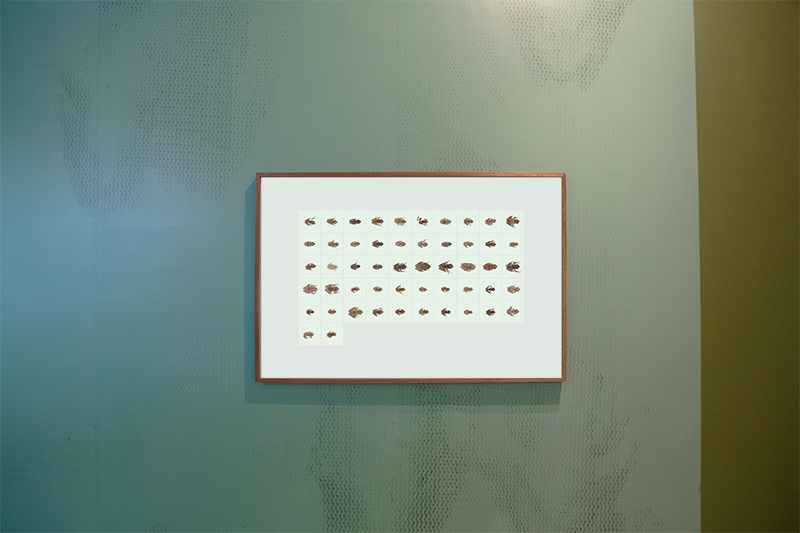

The exhibition is split into three parts — the first part is titled Disturbances, comprising images and objects that explore various taxonomies humankind has imposed on nature, such as native and invasive, noxious and useful. The work includes images of the spotted tree frog, an invasive species in Taipei crowding out the native white-lipped frog. These were created when “Remove Every Frog” Zhao joined a group of volunteers in Taipei who meet regularly on night hunts to capture invasive spotted tree frogs.

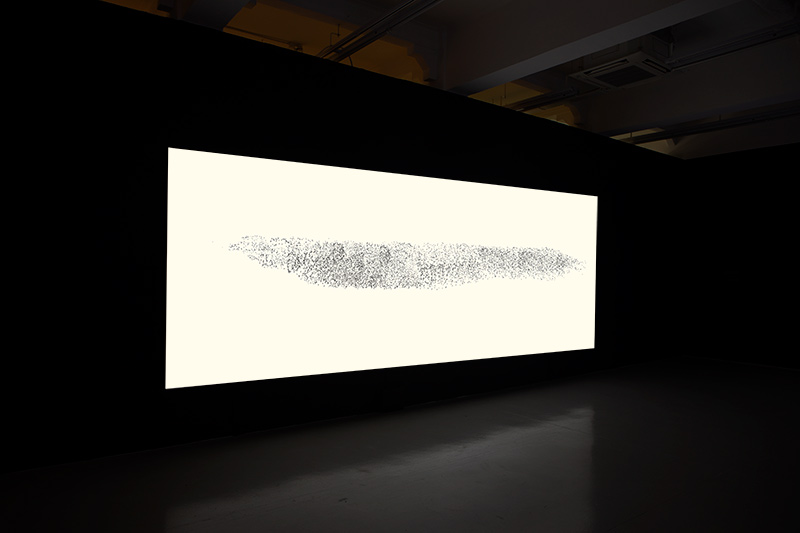

The second section, The Lines We Draw, is a series of large-scale lightboxes depicting bird migration in Yalu River. Located between China and North Korea, the Yalu river serves as a border; a politically charged space both on and above ground. For the migratory godwits and great knots, the river carries another meaning; it is a checkpoint in their annual journey that spans across the globe from Alaska to New Zealand. During migration season in 2019, Zhao and a local researcher visited the mouth of the Yalu River to document the phenomenon.

The last section of the exhibition is titled A Monument to Thresholds and explores extinctions and conservation efforts to prevent them. Gathering objects and narratives from different parts of the world, this section attests to the ambiguities of ecological conservation, and the extreme measures preventing species wipeout.

Zhao is particularly interested in threshold states, as both migration and extinction involve the crossing of boundaries. Exploring the spaces between invasives and natives, foreign and local, life and death, his works embrace a multitudinal perspective on the world. Although his images are drawn from specific locales, they are not constrained by their geographies. They remain mysterious, inviting contemplation without closing off interpretative possibilities, allowing for a position that is perpetually changing and unfolding.

In humankind’s pursuit for objectivity and order, whether within the field of science or politics, they have drawn lines across landscapes, communities, and disciplines. Zhao’s practice scrutinises the scientific method by infusing it with the aesthetic sensitivity and poetics of his images. In light of the ongoing Anthropocene extinction, the beauty in Zhao’s works is fraught with tension and complexities; beneath the familiarity of animals and cabinets of curiosities lies the negotiation between humankind’s understandings of existence and the latter’s perpetual changeability. Zhao problematises the safety of anthropocentric knowledge through representations of the other; reflecting on the lines and logics demonstrated by beings other than ourselves.

Bringing together recent new work spanning photography, video and installation, this exhibition explores migration and extinction in the natural world. Zhao shows how humankind has affected these two phenomena, as well as their continuation independent of human intervention -- resulting in complex, hybridised situations beyond conventional classifications. Drawing from narratives from China, Taiwan and Singapore, Zhao’s work spotlights situations of ecological interest: from the spectacular migrations of godwits and great knots seen over the skies of the Yalu River estuary to the “Remove Every Frog” eradication measures against the invasive spotted tree frogs in Taipei. In these works, movement, change and death form a vast, never-ending cycle to which humankind’s imposition of categories only simplifies and misrepresents. Zhao is particularly interested in threshold states, as both migration and extinction involve the crossing of boundaries. Exploring the spaces between invasives and natives, foreign and local, life and death, his works embrace a multitudinal perspective on the world. Although his images are drawn from specific locales, they are not constrained by their geographies. They remain mysterious, inviting contemplation without closing off interpretative possibilities, allowing for a position that is perpetually changing and unfolding, like the patterns formed by birds moving across the sky.

Part 1

Disturbances

Since the 1950s, due to increase in human travel and trade, animals and plants have crossed into new territories, creating new ecological categories of ‘invasive’ and ‘native’ species. Most conservation efforts are aimed at destroying the former and protecting the latter, though increasingly, more ecologists are conceding that these categories are fluid and unstable. This section explores the instability of these man-made taxonomies, as well as the measures taken to protect the boundaries between foreign and local, noxious and useful.

1. In 1956, American zoologist Marston Bates published Man As An Agent in the Spread of Organisms, one of the first reviews of the impact of introduced species. In 1958, English ecologist Charles S. Elton published The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants, expanding the notions of animals as aliens and invasives.

2. From 1910-60, German entomologist Dr Herbert Weidner studied pest insects and their effects on human life. Considered the father of “urban ecology”, he collected specimens of these insects as well as the objects they damaged. His insect collection is now housed in the University of Hamburg and divided into four categories: ‘Insects that destroy food’, ‘Insects that destroy wood’, ‘Insects that destroy our materials’ and ‘Insects that cause harm to people’.

3. Spotted Tree Frogs (Polypedates megacephalus) collected in a single night

White-lipped Tree Frog (Polypedates braueri)

The spotted tree frog was introduced into Taiwan, and its more efficient breeding endangers the native white-lipped tree frog. To control the population of the spotted tree frog, in 2011, Taiwan’s Forestry Bureau announced the “Remove Every Frog” campaign targeting spotted tree frogs, children and adult volunteers form teams to capture these frogs.

4. A hybrid of the Chinese Blue Magpie (Urocissa erythroryncha) and Taiwan Blue Magpie (Urocissa caerulea)

Chinese blue magpies from the Western Himalayas, brought to Taiwan as pets, escaped and bred with native Taiwan blue magpies in the wild.

5. Believed to be escaped pet birds, Chinese Blue magpies started appearing in Singapore in the late 1990s and thrive well in secondary forests. In this video, one such bird is seen eating the tadpoles of the spotted tree frog, a species native to Singapore.

Part 2

The lines we draw

The wetlands in Yalu River, Dan Dong, is an important bird migratory site for the godwit and great knot. These birds migrate between New Zealand, China, North Korea and Alaska every year, with godwit’s migratory flight being the longest nonstop migration of any bird in the world. As more wetlands and coasts in South Korea and China become concretised, the wetlands in Yalu River remains one of the last sanctuaries for these birds.

I went to the estuary in April 2019, during the time of the migrations. A researcher, who has spent more than 10 years counting the birds according to a complicated system, tells me that the bird numbers are dwindling every year. This year, he counted 54,231.

The best viewing time was during high tide in the morning. Every time the tide came in, great flocks of birds flew up from the shoreline, forming huge murmurations. The spectacular sight was witnessed by huge crowds of onlookers. Sometimes incredible shapes were formed, but I wondered if these patterns were random or intentional. The onlookers could see many shapes and lines that I wasn’t able to see.

I tried my best to photograph the lines that the birds drew in the sky.

Part 3

A Monument to Thresholds

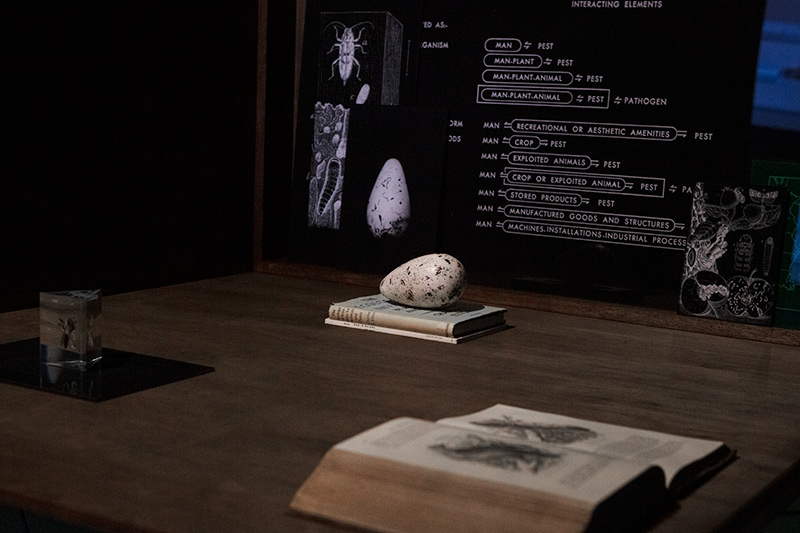

Extinctions and invasions are both ideas that test the limits of the current narratives we use to talk about relationship with nature. This work interweaves various narratives and histories to talk about this complexity.

1.On Sept 1, 1914, the last known passenger pigeon died at the Cincinnati Zoo in the United States. Once the most abundant bird in North America and possibly the world, it was estimated to have numbered three to five billion at the height of its population. The birds declined as a result of hunting and widespread deforestation.

2.On July 3, 1844, fishermen killed the last pair of great auks at Eldey Island, Iceland. For centuries, the bird was hunted for both meat and bait. Early museums and collectors contributed to the birds’ decline as museums sought to preserve and display the skins and eggs of this bird. Only 78 skins and 75 eggs remain in collections worldwide. This is a replica of an auk egg by American naturalist John Hancock, who was famous for plaster casting and hand-painted fake eggs that were indistinguishable from the originals.

3. In the winter of 2017, some 114 tons of clams were dropped by volunteers in the mudflats of Yalu River, Dandong. The place is a vital feeding site for arriving godwits and great knots, migratory birds that need to refuel during their long journey between Australia and Siberia. Clam numbers have been decreasing due to severe winters in the past few years.

4. Originally native to waters in Russia and Ukraine, Zebra mussels have spread to many places, aided by the discharge of ballast water from cargo ships from Europe. It has a bad reputation as an invasive that crowds out native species, and damages infrastructure such as harbours and waterways. On the flip side, it also thrives in the most polluted of waters and in certain environments, helps to clean the water up. A filter feeder, it removes contaminants by sucking nearly a litre of water each day in search of plankton.

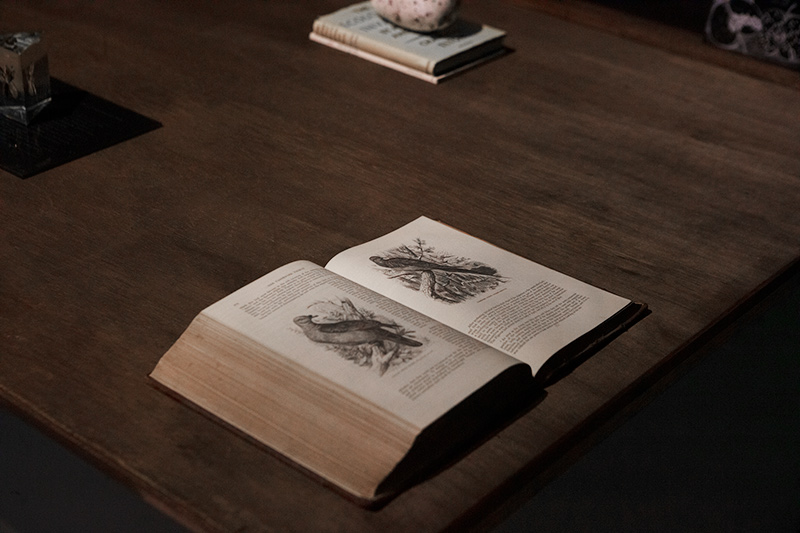

The Illustrated Natural History Vol 2.Birds. J.G.Wood 1867. A book that was published before the Passenger Pigeon went extinct. The book chornicles and speaks of the Passenger Pigeon population in the billions.

Copyright 2020, Institute of Critical Zoologists